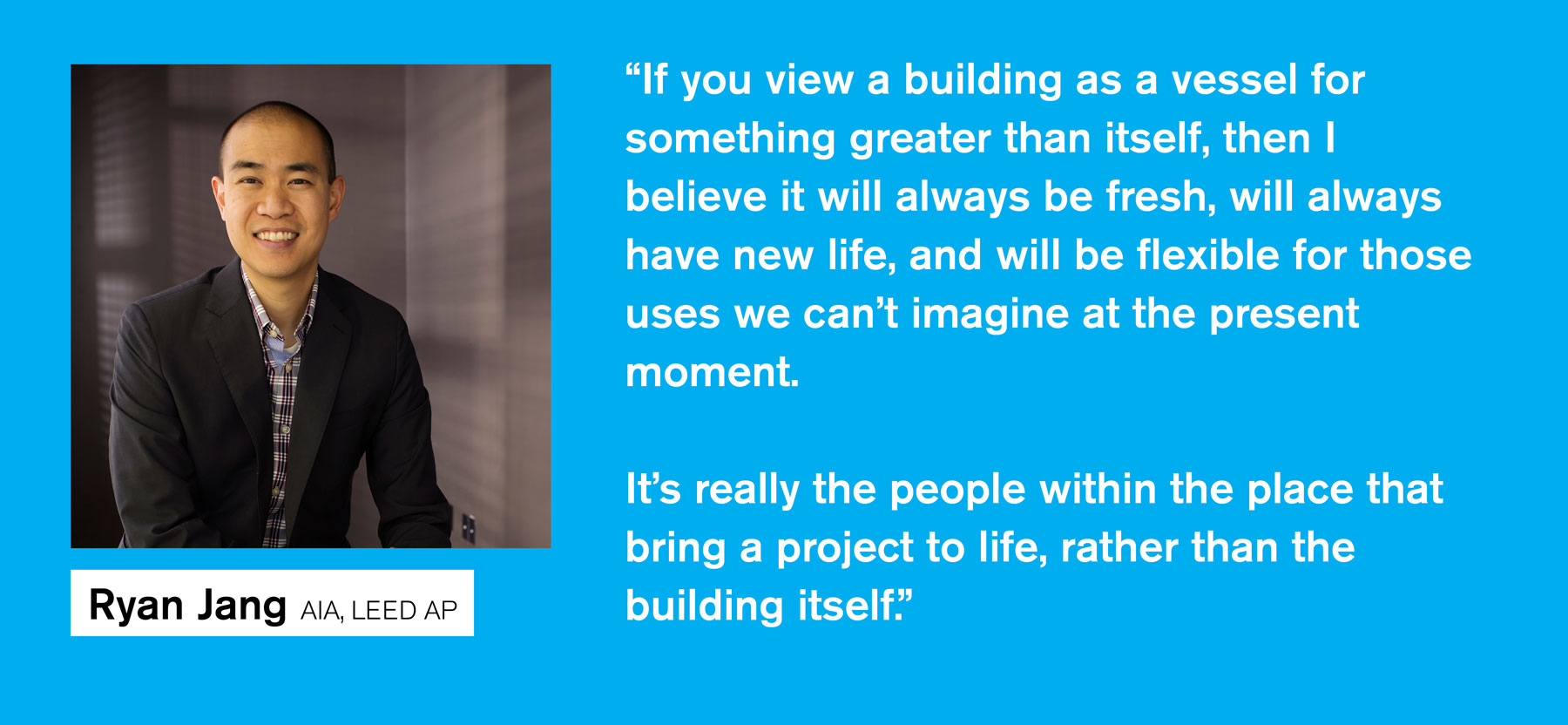

Q&A: Ryan Jang

LMSA Principal Ryan Jang discusses how buildings can express the values of their users and communities, designing for future flexibility, and why he once considered a career in ophthalmology.

Q: What led you to become an architect?

I was fortunate enough to have an uncle who was a civil engineer. Uncle Art was a civil engineer, working at the San Francisco Airport while the International Terminal was being built in 90's. He would bring me through construction sites when I was growing up. In high school, I took a class called Art and Architecture, and I thought, how hard can that be? Just draw straight lines, right?

Q: What drew you to the kinds of projects you’ve focused your career on?

There are many ways architects contribute to our world, but I was drawn to this type of practice because of its focus on bringing design excellence to those who might not otherwise have a chance to experience it. In high school, I had the great opportunity through the Enterprise for Youth program to spend a summer as an intern at HOK. It was a wonderful experience, and I had a wonderful mentor there. Who doesn’t want to work on designing a skyscraper? As I graduated from architecture school, I became more enamored with smaller-scale work. I’ve pretty much worked exclusively for smaller firms doing the kinds of work that LMSA does—schools, community gathering places, educational facilities.

Q: How does your community engagement shape the buildings you design?

In my recent projects, I’ve become even more interested in how buildings can better express the values and the culture of the organizations they serve and the neighborhoods they are in. For example, I’m working on a large affordable housing project in the Mission District close to our office. We spent a lot of time in the early community meetings talking about how to make it appropriate for the neighborhood. We’ve also been able to engage with a number of the people who may be living in the building. They said they want a building that serves the specifics of this particular neighborhood and this particular time. One way we’re doing that is by working with local organizations like Galería de la Raza to procure a mural that will represent this community.

Q: How have you seen a building you worked on evolve after completion?

Two come to mind. My first project at LMSA was the Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation at U.C. Berkeley. The building opened in 2015. Every so often, I get the chance to walk through the building. I’m always struck by how they are using spaces in ways we hadn’t intended. We built in enough flexibility that studios meant for teaching could be turned into workshops as new equipment came in—sometimes very large equipment. The structure is strong enough to support it. I don’t know how they got some of it in the door, though. Another project is the San Francisco Art Institute at Fort Mason, which we completed in 2017, the renovation of a historic U.S. Army warehouse to house studios, galleries, teaching spaces, a theater, and a workshop. Now we’re getting involved once again to see how these spaces could be adapted to house other potential educational institutions. We look at projects not only as objects that represent an idea for a particular client, but also as containers for uses that can change over time. If you view a building as a vessel for something greater than itself, then I believe it will always be fresh, will always have new life, and will be flexible for those uses we can’t imagine at the present moment. It’s really the people within the place that bring a project to life, rather than the building itself.

Q: Is there a project that’s closest to your heart?

This changes over time, but it's probably always the one I'm working on currently. Right now it's a new community center in Mosswood Park in Oakland. It’s about 12,000 square feet, but it’s packed with potential. There will be great after-school programs, and a social hall that can accommodate a variety of uses. The building is set in the middle of a 14-acre park, with trees that are hundreds of feet tall. So we’re designing it to be deferential to its natural context, while also adding a sense of exuberance and transparency to highlight all the great things that will be happening within.

Q: If you hadn’t become an architect, what profession do you think you’d be in and why?

I would have been an ophthalmologist. I have the worst eyesight of anyone I know. And during the summer that I had my first architectural internship, the other half of my summer job was doing administrative work at the Beckman Vision Center at U.C. San Francisco. I think the two professions have a lot in common. I’m fascinated by the ways things work, whether they’re buildings or bodies or anything else.